2019

Fall

Review: CURRENT:LA FOOD

ICA LA, Los Angeles

In Los Angeles a Thrilling and Unusual Triennial Considers Food in the Expanded Field

Cooking Sections, Mussel Beach, 2019, installation view

Art veterans know that the standard formula for a biennial or triennial is a sprawling show crammed with the newest and hottest emerging artists, plus a few established figures and a wildcard or two. Such events present themselves as the definitive statement on the moment, even as they often rely upon the recycling of well-trodden curatorial tropes. However, the second edition of Los Angeles’s public-art triennial, CURRENT:LA FOOD, offered something distinctly different. It scattered works throughout the city, taking on the common yet compelling topic of food as its theme. Through all kinds of installations, performances and interactive projects, this unconventional triennial brought to the fore the many ways that food effects everything else that occurs in life. It was a show that presented the kind of experimentation one more typically sees in a healthy artistic practice than an exhibition.

Running for most of October, into early November, this second edition of CURRENT:LA presented public art in the most expansive sense—not as a sculpture in front of a museum that people pass by, but as something intimately interwoven into the city. With Asuka Hisa and Jamillah James of the local Institute of Contemporary Art as its lead curators, and the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs as its main funder, the show involved interactive events at 16 public parks or spaces, and it brought viewers-turned-participants from all over the area, who almost always ended up with at least a little something to eat.

It was an egalitarian affair, in other words, and importantly, one that felt welcoming to newcomers to contemporary art. It was also ambitious in scale, with 15 commissioned artists and 15 public programmers, including organizations like Across Our Kitchen Tables, which offers skill-sharing symposiums on food-based work; Los Angeles’s Sustainable Economic Enterprises, which partners with farmers markets, public schools, and CalFresh EBT (the state’s food stamp program), to help spread access to healthy and sustainably grown food to more and more people in LA; and a “super” market called SÜPRSEED, whose self-described aim is to “end America’s ‘food apartheid.’”

With so many sites, artists, and programmers participating, summing it all up is a tall task, but a few highlights can show the interconnected and varied perspectives that were on view, and how they dealt with critical questions and conditions facing both California and the United States. Labor was central to the show, and its links to immigration, identity, history, nutrition, climate, and sustainability came out in a number of different ways from project to project.

The artistic collaborative Nonfood, an algae-based product company spearheaded by artist Sean Raspet and writer and researcher Lucy Chinen, installed an algae bioreactor on the grounds of an out-of-the-way Westside ranch. Here visitors could see the environmentally sustainable crop being farmed as it doubled in size every 24 hours. At certain events participants could harvest some of their own, attend edible workshops where participants learned to substitute algae and other sustainable plant-based proteins into familiar recipes, and co-mingle at a seed-themed educational picnic.

Nonfood, untitled, 2019, installation view

Also looking at sustainability concerns, but with an entirely different approach, were Carolyn Pennypacker and Annie Gimas, who used a public park in Van Nuys for a collaborative performance titled ALL AGAIN. The piece incorporated choral hymns, group choreography, found object installations made of aging fruit, and sculptural columns and baskets made of plaster to bring an enhanced and poetic awareness of the inevitable waste inherent within consumption. Like several of the projects in CURRENT:LA FOOD, it was a reoccurring performance that also provided a unique opportunity to use its site as an ongoing community composting hub that will likely continue long after the triennial.

Carolyn Pennerpacker-Riggs and Annie Gimas, ALL AGAIN, 2019, performance documentation

Other pieces took a more historical approach, by touching on fields like geology and agriculture, as in the highly interactive work titled Mussel Beach, by the British duo Cooking Sections. Having been assigned Venice Beach as their point of intervention, the artists homed in on the famed weight-lifting area Muscle Beach. While researching its past, they learned that the Venice marina has long been a critical area for a particular California mussel species that is now seriously threatened due to longstanding environmental degradation. The duo carved out a route for their viewers that allowed them to see and experience all of the quintessential features of the coastal area. Retooling the now ubiquitous headsets offered at large museums for easy walk-along listening,

Cooking Sections, Mussel Beach, 2019

Cooking Sections drafted an audio track to guide viewers through the beach, piers, boardwalk, skate park, workout areas, and eventually the rocky cliffs that the mussels cling to as they filter seawater. While they enjoyed the sea breeze and watched the locals buff up, an almost-robotic-sounding female voice asked its listeners to consider their own muscles and their surroundings, and pointed out the sights, adding in historical and agricultural facts where relevant. There was a hidden symmetry here, with the mussels exercising their valves to ingest nutrients and filter out pollutants and plastics, while the bodybuilders and “modders” were pumping iron and binging on green smoothies and protein shakes. That culinary touch inspired the artists to offer visitors mussel tacos and mussel-infused shakes that were lightly briny, frothy concoctions that straddled the ever-so-popular divide between savory and sweet.

Nancy Lupo, Open Mouth, 2019

Still other artists took the food brief to the public in unusual and inventive ways. Nancy Lupo installed a series of 16 benches titled Open Mouth, whose 32 rounded elements reference the number of an adult’s teeth. Open Mouth enveloped the entryways and exits of part of the bustling Pershing Square in downtown L.A. and used both the border created by the configuration of the benches and the activated space therein to consider the symbolic metabolism of the city, brought to life through staged performances and readings.

Similarly sculptural was — Imperishable, Jazmin Urrea’s Judd-esque clear plinth structures filled with crushed-up dark red Flamin’ Hot Cheeto dust that smeared and crackled as it continued to soak up the sun’s rays throughout the duration of the exhibition.

Jazmin Urrea, Imperishable, 2019, installation view

Not everything took such an oblique approach, though. For New Shores: The Future Dialogue Between Two Homelands, which was set in the centrally located Barnsdall Park in East Hollywood, Max La Rivière-Hedrick and Julio César Morales produced a weekly series of evening picnic gatherings that featured foods prepared on different themes and with ethnic histories that celebrate those immigrant communities that thrive in the neighborhood, including Korean, Armenian, Thai, and Mexican. The artists also invited special guests to share readings, poetry, music, screenings, and performances whose underpinnings further tied food to the cultural narratives woven into migration.

Julio Cesar Morales, New Shores: The Future Dialog Between Two Homelands, 2019, installation view/event documentation

Why do a food triennial now, and why in L.A.? The world is getting fuller, and hotter, and we are seeing more droughts, fires, and floods that directly threaten crops and livestock, and that imbue individual food choices with political concerns. The city felt like an ideal place for it. Long stereotyped as the land of Del Taco and In & Out, it is home to the ever-flourishing cuisines of countless immigrant communities, and it has a burgeoning food scene at seemingly every price point. As for CURRENT:LA FOOD’s own finances, it appeared to be light on its feet—making a lot out of a little. There were none of the big-budget spectacles that so often dominate these events. It showed how a major exhibition like a triennial can function as something other than a donor-and-collector-oriented capitalist venture. Instead of a hulking display intent on minting markets for new artists, it operated in a fleeting, experiential mode, asking people to get together, to talk, and to eat.

January

New Scenario

Cameron Nichole is Chloe Sevigny is Bruce Nauman

In Summer 2018 New Scenario produced a video reenactment of Bruce Nauman’s 1968 performance, Playing a Note on the Violin While I Walk Around the Studio, which took place in New York City. New Scenario’s video was presented, without additional information, to eight international writers, who were thereby invited to use the video as a source of inspiration for a new text. None of the writers knew that they had all received the same video as source material.

New Scenario (Paul Barsch and Tilman Hornig), Cameron Nichole is Chloe Sevigny is Bruce Nauman, 2018 (video still)

Tracking Faces - Coordinates - Limens

New York is a tempting place. In the summer, especially, it is a catnip of sorts for all manner of strolling, frolicking, and lollygagging. The streets are full of millions of faces, and most, perhaps, are as eager to frequent as many indoor public spaces as possible throughout the course of their busy day, for even the mere brief respite provided by that reassuring hum from the industrial strength air conditioning provided by hubs like the CVSes and Starbuckses of the city. Summer is not for dwelling within, it is, in New York in particular, for going out into the world, and staying out all hours. Otherwise overlooked areas become commonplace hangouts, like stoops, corner stores and rooftops. However, over the years, as the city continues to get more packed with people and the faces of strangers roaming the crowded streets, and as it gets hotter as global temperatures rise and modes of transport multiply, it is important, whether a resident, a frequent couch surfer or just a one-time tourist, to keep in mind that as miniscule as you may feel amongst the thousands of busybodies walking up, down and across town, entering and exiting stores, banks, cafés, all the while texting and tweeting and talking to Siri and face-timing and taking pics and selfies, you are, nonetheless, easily pinpointable. You are a set of coordinates – the unique contours of your very own face – their virtual cipher.

It may seem like unwillful surveillance, but more and more we are opting to look squarely into cameras and screens in order to unlock the virtual realms within which so much of our lives now take place. And thought it seems so commonplace, and the exchange is completed so instantaneously, all the while, whether out on the street, up on a roof enjoying the view, or hiding out in the cool darkness of the movie theater on a sweltering night – we are essentially “in frame.” Being within the proverbial frame, so to speak, can be as threatening as it can be emboldening. Admittedly, this panopticonian way of life is not new, nor does its invisible limitations come as a surprise. However, as technology advances not only its actual capabilities, but its permeabilities, which seep as much into cultural norms and daily life as they do into the very threshold of our physical being, we become less aware of the consequences of our exteriors, and in that sense, perhaps they slowly lose their agency, or at least the kind of agency that we once found reassuring. And in that slight lapse of awareness between posting a perfectly filtered image and crossing the street to meet a friend, we send out a myriad of constant signals that are available for tracking at the ready.

Too much awareness of the bulls-eye-like aura we radiate through our central position within our own frame is always attempted to be kept at bay by both internal and external forces. Even the potential tightening of its collectively understood contours could have dire consequences. The subject of a work of art, figurative or otherwise, is liberated by such localized stature, but the similar spotlight within which we now exist and perform, whether via social media nexuses or by using our faces to access our bank accounts, is not comfortably couched in the artistic realm of the contemplative. Instead its hold on us can have drastic effects on our lives, and therein, what we conceive of as our inherent freedoms. The connection between these two types of frames has been parsed by many artists, but, looking back at the onset of video art, now a full generation past, there are few works whose ultimate meaning still speaks as simply and didactically about the issues that we face today as moving bodies within a surveilled frame, as those of Bruce Nauman.

Such work’s ongoing relevance is evident in its self-reflexivity, despite the major advancements in user-guided technologies over the interim. However, despite the proliferated parallels between our relationship to public space via technology then (the 1970s), and now (nearly two decades in to the 21st century), video art’s draw on younger contemporary audiences still seems to be a bit of an inexplicably slow burn. Though abstract art still looms surprisingly large, our cultural and behavioral tendencies have, arguable, never been more visually saturated. Like the frame we most often refer to these days – the one that fits so smoothly into the palms of our hands, and that we reach for and slide our fingers across for nearly every imaginable reason throughout every hour of every day – Nauman’s early video works, most of which consisted of the artist walking back and forth in small, composed spaces, are as much about the communal, and communication, as it is about the sensorial, by way of confinement.

Though he is known for being among those few contemporary artists whose work spans seemingly endless visual manifestations and forms of experimentation, and is thusly revered for resisting that controversial tendency toward over signature-stylization, Nauman’s early videos feature several unmistakable elements. Namely through his use of such basics as the staking out of a delineated space, the repeating of a movement or set of actions, and the incorporation of a directional sound source, these works, both in abstract, and even obtuse ways, evoke the systemics and the visceral feeling of mapping bodies and various modes for the extrinsic management of their lived experiences. In terms of space, Nauman extends his actions out at least to the generalized dimensions of “the” or “my” studio, but soon began constraining himself to a corridor or platform of sorts, either pre-existing or specifically constructed for performative use. Here again, its not difficult to see the congruence between the ways that we are so often existing today within virtual (online) frames, with their specific defaults, filters and regulations, and the ways in which Nauman infers his singular presence within another multitude of frames. Foremost is of course the physical frame of his studio or corridors, which dictates the breadth of his bodily movement, but more importantly, the implications and meanings behind them. The technological frame of that the camera itself imposes is just as central, as, without it, such meaning would never have been conveyed outwardly. But the larger, more conceptual frame of the art context within which Nauman chose to operate is most striking today, as it correlates with our attention-seeking social media behavior today as a telling jumping off point. With his movements, like much of the activity we present and absorb online, Nauman does practically nothing. Nothing of note. Yet, it is that incessancy that rings true, and makes him – and us -- seem less alone.

2018

January

In this, Untitled's second San Francisco iteration, taking place at a new (and improved, by all overheard accounts) venue at the city’s iconic, dome-shaped Palace of Fine Arts, the West Coast fair matures and hones its scope while also offering a refreshing range of exhibitors and avenues for art-making. Like its Miami counterpart, Untitled remains happily a friendly and unpretentious atmosphere to experience its rather humble arrangement of roughly forty booths brought to you by a variety art spaces, from the more traditional and well known commercial galleries like David Zwirner (New York and London) to community-oriented non-profits like Creative Growth (Oakland), academic-leaning institutions like CCA's Wattis Institute (San Francisco), or research and archival-based foundations like the David Ireland-centric, The 500 Capp Street Foundation (San Francisco).

While work spanning all media is on view—and while the large-scale, colorful abstract paintings that have reigned supreme, particularly within the market-driven environment of most art fairs, was nonetheless prevalent—sculptural figurativism was also a palpable through line. Here are six artworks on view that had us thinking about the body in unexpected ways.

Tim Hawkinson, Gumball, 2017

Denk Gallery, Los Angeles

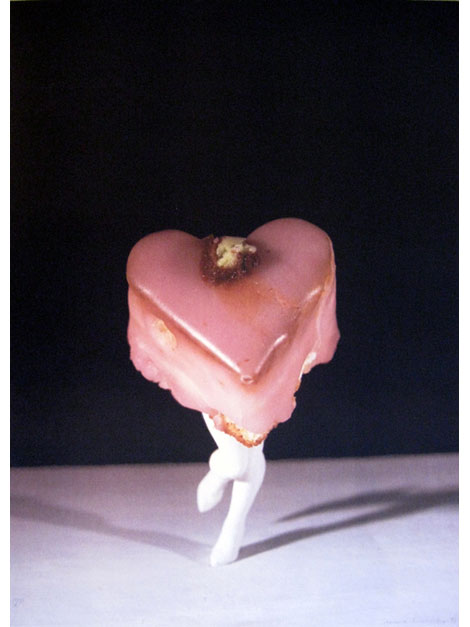

At Los Angeles’ DENK Gallery, much of the booth was animated by Tim Hawkinson’s playful, urethane sculptures of distilled and recomposed puzzle-like cast studies that also double as self-portraits of the artist's own body parts. Here Hawkinson has selectively isolated the mostly curvy areas of himself (his knees, elbows, belly, and butt), cast them in a smooth, recognizably bubblegum pink material, and conglomerated them into a ball-shaped miniature “being,” who is then grounded by his feet and flanked on one side by his upright, palm out, hand. His play on the misuse and/or reuse of body parts themselves and the notion of the quintessential artist's self portrait is further exaggerated by the work's overall relationship to candy, an enjoyable ingestible that may often conjure dietary fears and resemble pink, fleshy, jellyfish delights.

Julie Weitz, Screen Gestures 1 and 2, 2018

Luis de Jesus, Los Angeles

Another Los Angeles gem of a gallery, LUIS DE JESUS, went a step further in risqué, body-oriented depictions, with new work by Julie Weitz. Among her compelling and brightly colored videos and some dildo-cast candles available in a range of psychedelic, swirly hues, is an intimate, smaller-scale duo of video-objects titled Screen Gestures 1 and 2. With these tablet-like pieces, Weitz marries her sensual moving imagery with sculptural smoothness, achieving a video that depicts the sometimes uncomfortable, entropic aspects of feminine beauty (as is here evidenced by an acute study of hands and fingernails), and a slick, “contemporary” flat-screened device much like the companions that live in our pockets and handbags and that assist us in just about everything we do throughout our daily routines.

Michael E. Smith, untitled, 2017

Andrew Krepps, New York

Other takes on “the body” were much more opaque and relative, as is often the case with the plebeian guise of Michael E. Smith's work, which was on view in not one, but two different booths at the fair. Almost all of Smith’s pieces are untitled, but this wall piece, like much of his work that utilizes found objects like clothing and toys, is more a referential nod to one's own interactions with everyday objects (the materials list an artificial heart and a sprinkler head), than an introspection on one’s own form.

Michael E. Smith, untitled, 2017

500 Capp Street Foundation, San Francisco

Smith’s lexicon-esque oeuvre of seemingly random things extracted from “the regular” and thwarted (half hap-hazardously, half with extreme care and consideration) into “the representational” was also at play in the booth of San Francisco’s The 500 Capp Street Foundation. The booth is set inside of the house-cum-artwork of the belated artist, David Ireland, where Smith currently has an unconventional solo show in which his own works are sparsely and thoughtfully interjected into those of Ireland’s works/furniture/interior design aesthetic. Here the foundation showed all five in the edition of, again untitled, plastic pitchers that Smith made specifically for 500 Capp Street to present and sell at Untitled. They seem ordinary enough, except upon much closer inspection of their slightly eschewed, roundish, brown bases, it turns out that they are in fact made of taxidermied bison scrotum—complete with little tufts of hair and all! Here, the connection of all bodies, human and otherwise, and the imparting of the masculine onto the idea of both minimalism and functionality within the history of art, seems both understated and yet aptly accessible.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tubal Invasion (Collage), 1985

Anglim Gilber, San Francisco

San Francisco’s Anglim Gilbert presents work by an artist with whom they have a longstanding relationship with, and whom is only now, finally beginning to get the kind of real institutional exposure and credit that she so well deserves. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s black-and-white images from the 1980s and '90s, included here amongst a large and perhaps purposely slightly cluttered installation of other works on paper by fellow California artists like Bruce Conner, are yet another example of portraiture and the image of the figure, popping its head (pun intended) into the mass of shapes and images that cover the various booths at Untitled.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Synthia Stock Ticker, 2000

Hershman Leeson, who is perhaps best known for her unconventional and almost spy-like tactics of uncovering early feminist identity politics issues, here titles two photos of a woman who may or not be Leeson herself, as Tubal Invasion and Shutter. Both terms could be understood as relating to the technology of photography and image-making on the one hand, and on the the other, as conjuring ideas of the female body as vessel, perhaps even as victim. More generally, these works evoke the kind of anxiety that being photographed—and the assault associated with the infiniteness of ones image being captured within a singular moment in time—that photography undeniably provokes.

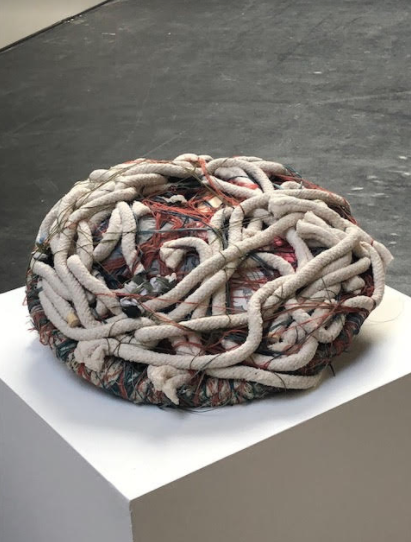

Judith Scott, untitled, 2003

Creative Growth, Oakland

Oakland’s now somewhat infamous arts organization Creative Growth, the non-profit that supports and presents work by artists with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities, returns to Untitled yet again to much acclaim. This time one of their artists, Judith Scott (1943 – 2005), a compelling sculptor with downs syndrome who was also deaf, is featured as one of the artists in Untitled Special Projects. Scott’s works are complex and colorful bundles whose presence draw in the bodies of those around them and exude a kind of breathing warmth and hug-like tension, making the artist's care and force in producing them all the more visceral. Here three of her woven, bundled forms that utilize fiber, found objects, and plastic, are presented on pedestals low to the ground, shifting one’s sense of space and time while carving a route through the crowded art fair atmosphere.

2017

June

Speaker, In conversation with Ivana Basic, Marlborough Gallery, New York

May

Ivana Basic: Through the hum of black velvet sleep

Marlborough Contemporary, New York

May 25 - June 24, 2017

Text by Courtney Malick

Dyad figures afloat,

Finally they are still, motionless

Their sedentary shells swath their sides,

The core it is tethered to appear further and further away, its arms, exceedingly outstretched, are cold and surely waning...

In this space

Feeble air falls rather than fills its gaps

As it sinks into softness — all movement stunts

turns to torpor.

Pressure surrounds and leaves me hardened, petrified

A sigh fills a slippage that wrings my bent neck

This vessel may shatter

this moment,

or the next

Here I stand within the draining of the light

of will

of flux

of vim

Uplifted, feet barely brush the ground below.

As if holding on to it.

Belay my light...

And the ground is gone.

....All that remains is a deafening hum, as bodies of dust slowly swirl.

Marlborough Contemporary is pleased to present its first solo exhibition of new work by Serbian born, New York-based artist, Ivana Bašić. Through the hum of black velvet sleep, furthers Bašic’s study of both the experiential and atmospheric aspects of the body as it dwindles and subsists in its fringe states. With forms that are as relatable as they are alien, this show builds upon the premise of dust as the absolute reduction of the world, a substance in which the world is anonymously contained, since the origin of each particle is unknowable. Similarly, the body’s reduction to dust renders it its composite, suggesting that the unknowable nature of the universe is conditioned upon the unknowable nature of the body and its alien alloy. With this in mind, Through the hum... mirrors the phases and effects of the body under pressure as it transitions from the states of being and porosity to pure density, stone, and ultimately a return to nameless fine matter.

Like nesting dolls, the individual works in the exhibition each embody the cyclical stages of becoming, being, declining, and ceasing to be. Upon one’s first step into the interior, the viewer encounters the central work, I will lull and rock the ailing light in my marble arms. The twin protagonist works on view are at first obstructed from sight. Only when circling around the space does one encounter the two hunched, pale, rigid forms projecting outwards, suspended seemingly in mid-air. In stark contrast to their bodily sensitivities, their vehicles, of sorts, are brutal, steel shells closely encapsulating them.

Their heads are engulfed by delicate glass vessels — like gas masks. In them their breathing dissipates as exhalations turn to dust. It is clear from the dangling limbs and bowed heads that these forms are facing imminent expiration. The metal shells that uphold them are as much an antiseptic container, such as one that a body may eventually end up within, as it is a cradle, where the body flourishes in its inception. As Bašic focuses on abstracted narratives of becoming and ceasing to be, time looms overhead with two instances of a work titled A thousand years ago 10 seconds of breath were 40 grams of dust. Like hourglasses, each of these mechanisms are paired with one of the suspended bodies, weighing the remaining time until their disappearance. Moments are measured by the brief respites in between the rhythmic impacts inflicted upon the surface of the blush colored alabaster. The force slowly crumbles the stones, turning them into fine dust that piles on the gallery floor and stirs into the very air that fills viewers’ lungs, tendering to the cycle.

—Text by Courtney Malick

April

Contributor, "Slicing Through the Middle: Ties that Bind the Future of Reliable U.S. Protein Sources, The Inherent Dichotomy of the Female Posture, and the Confrontational Sculpture of Ivana Baisc," "re: the FURIES," panel discussion organized by CASSANDRA press, Contemporary Artists' Book Conference, MOCA Geffen, Los Angeles

January

Moderator, "One Stop Shopping: Information in Social Media Today," panel discussion with Lucy Chinen, Aria Dean and Ryan Lincof, Photo LA Fair, Los Angeles

Lucy Chinen, found image

"Brighter Lights" promotional image,

PRESS RELEASE:

With almost half of the country receiving its [a significant amount of] news from some social media source, it is now more than ever important to examine some of the formats and underpinning, algorithmic structures of those platforms, such as Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram. This conversation aims to better understand why social media, as a vehicle for the circulating and garnering of information, is so captivating and, more importantly, how the influential cross-overs between spectacle and affect that it often facilitates can so drastically shape both opinion and fact (or lack thereof, as the case may sometimes be).

Moderator, "Out of Absentia: In response to Inauguration Day and the global Art and Culture Strike," organized by 501(c)3 Foundation, Los Angeles

PRESS RELEASE:

"Out of Absentia"

January 20th, 2017

A panel moderated by Courtney Malick with Andrew Berardini, Cyril Duval, Leah Garza, Paul Krist, Shyan Rahimi, and Amanda Williams

Inauguration Day

January 20, 2017, 9PM

Bethlehem Baptist Church, 4901 Compton Avenue, Los Angeles

Drawing Courtesy of the Architecture and Design Collection/Art, Design and Architecture Museum/University of California, Santa Barbara

On the day of the inauguration of the first ever American president who comes entirely from the private sector and who brings with him advisers and policy-makers who are also mostly high-earning finance world executives with as little experience in government and public service as the president himself --- a new president who takes office with record low approval ratings -- this panel of curators, artists, architects and activists come together to assimilate this moment in history to offer and reciprocate progressive, supportive and indulgent reactions from both speaker and viewer. "Out of Absentia" is an opportunity for LA cultural producers to thwart the art and culture strike that many individuals and institutions have bound themselves to on this critical day in our political history. Instead, we want to begin on the very day that this controversial new president is sworn into office, the long path forward in opposition to the inevitable corporate greed and unfairness that will shape much of American policy over the next four years. This talk welcomes discussion of, expressing anger at, brainstorming for, and publicly grieving the loss of decency to which the election of Trump signals.

Andrew Berardini lives and works in Los Angeles. Father of Stella. Writer of quasi-essayistic prose poems about art and other sensual subjects, occasional editor, reluctant curator with past exhibitions at MOCA - Los Angeles, Palais de Tokyo - Paris, and Castello Di Rivoli - Turin. Formerly held curatorial appointments at LAXART and the Armory Center for the Arts and on the editorial staff of Semiotext(e). Recent author of Danh Vo: Relics (Mousse, 2015) and currently finishing another book about color. Regular contributor to Artforum, Spike, and ArtReview and an editor at Mousse, Art-Agenda, Momus, and the Art Book Review. Warhol/Creative Capital and 221a Curatorial Grantee. Faculty at the Mountain School of Arts since 2008 and the last three years at the Banff Centre.

Leah Garza is an L.A. based social justice teacher, healer, and activist. She received her Master's in Education from UCLA and has worked in education for 17 years, in both non-profits and in the classroom. Through her healing practice, she has been guided to work for justice through healing social, personal, and historical traumas with individuals and communities. Her most recent call to action is the LoveCast, a weekly discussion about the abundant universal supply of love as a tool for social justice.

Courtney Malick is a curator and writer whose work focuses on sociologically, content and narrative-driven artistic practices that most often employ performance, video, installation, new media and the intersections therein. She is a contributor to publications such as Art in America, Art Papers and SFAQ. Recent projects include The Pleasure Principle at FARAGO (Los Angeles, 2016), and a two-part curatorial endeavor titled, In the Flesh that took place in Los Angeles (2015) and Miami (2016), respectively.

Paul Krist is a German designer, filmmaker, and teacher at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). He studied architecture at the University of Applied Arts Vienna (Angewandte) and graduated with distinction from the Masters Program at SCI-Arc. With an interest in interiors, Paul’s work explores the potential of cinematic film as a medium for architectural design. He uses filmed footage and contemporary visual techniques to investigate the role of objects in the space of a room. Room XYZ – a collaboration between Paul and Devin Gharakhanian – is a virtual reality (VR) installation for One Night Stand for Art and Architecture that was featured in Archpaper. He assisted in the production of Where The City Can’t See, a fiction film directed by Liam Young and shot entirely through laser scanning. Paul’s recent short film, Ensemblespiel, was featured in Archinect and was a Gold Winner at the International Independent Film Awards.

J. Shyan Rahimi is an artist and founder of 501(c)3 Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to producing projects that take place in historically-charged, often architectural landmark spaces in the Los Angeles area and beyond. Ignited by guest curators, 501(c)3 presents informed programming based on site-specific research, resulting in temporally-sensitive exhibitions, performances and discursive events that respond directly to the arch of narratives and circumstances that characterize the unorthodox spaces utilized. Recent projects include 9800, which involved the monumental takeover of Welton Becket's iconic building near LAX by seven curators and over 100 international artists.

Amanda Williams is a progressive educator, writer and artist based in Los Angeles. Her holistic critical approach to each discipline draws on history, physical and emotional wellness, and lyric to hold government and society highly accountable for outcomes for people of color. She is currently working on several media and publications.

2016

November

Moderator, "Context in Flux: Contemporary art in space and online," panel discussion organized by ArtTable LA, with Jeff Baij, Ceci Moss, Gene McHugh, Ryder Ripps and Michael Staniak, Steve Turner Gallery, Los Angeles

(from left to right): Courtney Malick, Michael Staniak, Gene McHugh, Jeff Baij, Ceci Moss, Ryder Ripps

PRESS RELEASE:

Image: Ryder Ripps, Barbara Lee, 2016, installation view

Steve Turner Gallery, Los Angeles

Join us for a public panel, organized by ArtTable's Southern California Chapter, that explores the dynamic relationship between contemporary art, new media methodologies and online technologies.

Since the start of the millennium the internet has become a force that has permeated practically every aspect of culture and society. Internet-based artistic practice has gained ubiquity as a new generation has emerged that interweaves art with virtual reality. These artists directly engage with social media, online commercialism, rapidly advancing digital and mobile technologies. New media art challenges prevailing definitions of artmaking by extending the bounds of its audience, its cultural reach, and its integration with everyday life. This panel will explore the persistent, dynamic relationship that continues to form between art, online culture, and emerging technologies, and will consider how current configurations may evolve in the future.

Moderated by contemporary art curator and writer, Courtney Malick, the panel includes Gene McHugh, author of Post-Internet: Notes on the Internet and Art 12.29.09 > 09.05.10 and head of Digital Media at the Fowler Museum, UCLA; Ceci Moss, former curator at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco and one-time Senior Editor of the art and technology organization Rhizome at the New Museum; and artists Michael Staniak, Ryder Ripps and Jeff Baij, whose careers are geared towards digital and mediated modes of art making. The panelists will discuss timely issues such as: How does our reliance on the internet as a tool change the ways that art is made, seen, and experienced? What new challenges does the internet create for artists, and is social media's impact on the art world for the better or the worse? Does authenticity have a role to play within this context? How is mass engagement with online culture positioned vis-à-vis art institutions and the art market?

Text by Courtney Malick

September

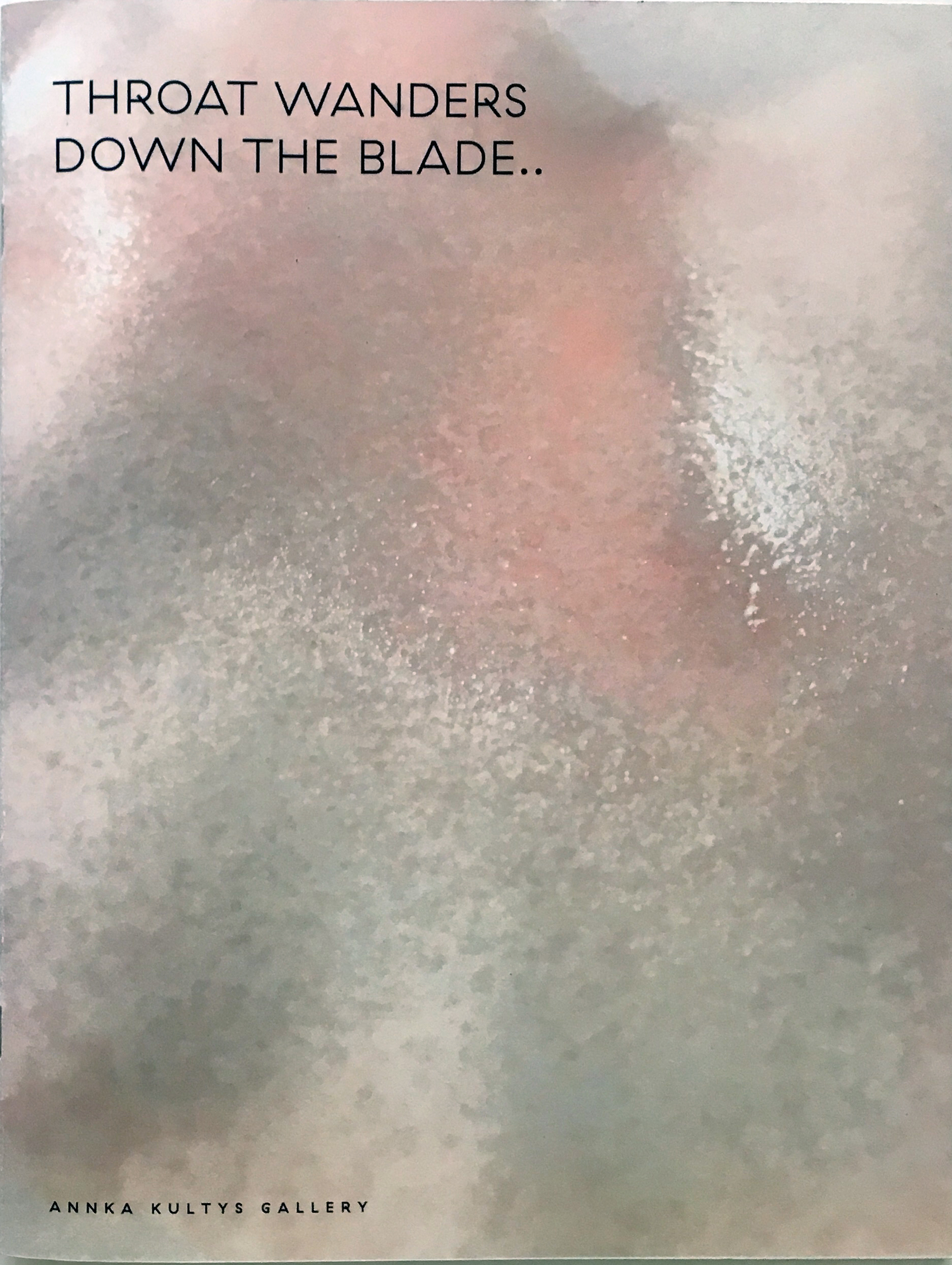

Ivana Basic

catalog essay

Annka Kultys Gallery, London

Throat wanders down the blade...

Text by Courtney Malick

Illustrations by Ivana Basic

PRESS RELEASE:

Annka Kultys Gallery is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition in the UK of New York-based artist, Ivana Basic. For her exhibition Throat wanders down the blade.. Basic features a new body of sculptural work and an accompanying book with original drawings by Ivana Basic and writing by Courtney Malick.

In Throat wanders down the blade Basic methodically constructs Bridle, the character that embodies the tension of both the fundamental fragility of life as well as the violent force behind its suffocation.

Throughout the exhibition and book, the character of Bridle is constituted on multiple levels. With Basic’s signature alien corporeality at the fore of her wax sculptures, Bridle gains physicality as she inhabits multiple pieces in the show, moving from one form to the other, the glass air vessels suspended on the walls show progression of Bridles breath, and lastly the written work that follows the exhibition, represents Bridle’s voice.

Bridle, is most precisely disseminated in Basic’s central sculpture in the show. The piece spans the width of the exhibition space with entities joisted against opposite walls by a long metal rod that pierces each at its core. In this way both forms are at once wounded yet simultaneously tenderly bonded andjoined. It is this same, turgid dichotomy found therein, that also characterizes Bridle’s internal tension as both pieces represent reflections of each other and of her being.

As one wanders through its uncanny interior, forms cushioned with wall padding and glass-blown baubles affixed to the walls like guiding sconces, one senses more and more the character of Bridle and the binary environment from which she is born. If in the written piece we can hear her voice, it is in this exhibition that we not only see glimpses of her ever-shifting and inverting physical form, but also feel her breath upon our face as it is trapped and released again and again from within the crumpled glass vessels on the walls. Her hair wisps past us as we turn to take in another sculpture, and ultimately trace her footsteps through her strange yet all too familiar journey.

Text by Courtney Malick

Images:

Ivana Basic, Populations of phantoms resembling me #1 and #2, 2016

Throat wanders down the blade..., Annka Kultys Gallery, London, 2016, installation view

Ivana Basic, Populations of phantoms resembling me #1 , 2016 (detail)

Ivana Basic, Populations of phantoms resembling me #2, 2016 (detail)

Ivana Basic, Stay inside or perish, 2016

Throat wanders down the blade..., Annka Kultys Gallery, London, 2016, installation view

Ivana Basic, Stay inside or perish, 2016 (detail)

Ivana Basic, Stay inside or perish, 2016 (detail)

Guest Editor, Arts and Architecture, Fall Issue

"Sarah Oppenheimer's Unique Brand of Infrastructural Friction" at Perez Art Museum Miami

To intervene in the physical (and conceptual) space of the white cube is every artists' job. Their work can otherwise be thought of as a usually temporary imprint upon the structure or interior in question. In that sense, every exhibition is, to some extent, site-specific, even if it travels in the same formation to multiple venues. However, the notion of 'the white cube' and the mysteries or mysticism of what can happen therein, is a topic of artistic interest of which we have recently seen much less. In favor, instead, is work that has sprung from an artist's unique perspective, challenges, or agitations of systemic realities that exist and affect life outside of the white cube. In that way, the function of the exhibition space today more often takes on the role of the telescope rather than of the incubator.

Architecturally-minded artist, Sarah Oppenheimer, came of age in the late 1980s and early '90s when the agenda of the white cube was shifting from an introverted to an extroverted point of view, which began with the visual manifestations of social-centric theories like identity politics and relational aesthetics. Art of that time began to override the singular importance, primacy or preciousness of the art object that had prevailed throughout the 1960s and during most of the '70s with its focus on painting and sculpture, even as performance took off at that time. Placing Oppenheimer within this transitional context, we see that, aptly, her work often takes the structure of the exhibiting institution as both its intellectual jumping off point and its logistical parameters.

This fall Oppenheimer brings her sensitivity to the nuance that simultaneously define and differentiate individual and collective perspectives to the Perez Art Museum Miami, with a new, site-specific commission, rather blandly titled, S-281913. To be bland, it should in fairness be noted, is often to be institutional, and in this way Oppenheimer's project for PAMM is fittingly named. However, those fortunate enough to have visited the museum know that it appears much more like a tropical resort than an insular, hard-edged building that delineates between interior and exterior. When asked about her approach to this uniquely expansive environment, as opposed to the isolation of the traditional white cube, Oppenheimer made it clear that she understands how PAMM is special, noting, "the uniqueness of the [Perez] building largely results from its relationship to site." In turn, she also points out that, as she says, "the sameness of the building speaks to [its] less visible, but no less significant features: [for example], the un-contained air transfer in the floor plenum and the overhead lighting grid." Though we know that S-281913 will be singularly tailor-made to PAMM and therefore fits into its space somewhat seamlessly, (even as it may complicate or confuse the building's architectural framework or how visitors thus move within it), there is also a neutralizing factor at work that speaks not just individually to PAMM, but to the larger formulations, expectations and demands of all art institutions.

From this set-up, it is clear that there is an air of Institutional Critique lingering within Oppenheimer's project. Institutional Critique, we should remember, is now mostly considered an historical term, referring to a certain group of artists, such as Hans Haacke, Marcel Broodthaers, Martha Rosler and Andrea Fraser, to name only a few. These artists and many of their contemporaries' practices were jump-started in the late 1960s with somewhat unsavory or uninvited institutional interventions that questions or blatantly criticized the very forums within which they operated. When confronted with the harkening to Institutional Critique that one might likewise read into S-281913, Oppenheimer is somewhat reluctant, claiming, "I prefer the term 'infrastructional friction.' While [Institutional Critique] has greatly influenced my thinking, architectural and institutional strategies have changed [significantly] over time. These merit a new engagement and perhaps a new language." Nonetheless, there is a sociological aspect to any museum that cannot be denied, and within any sociological schema there is also a question of status; to this Oppenheimer continues, "Notably, the tools that generate these buildings, the developers that finance [them], and the mediums that represent [them], are increasingly the same in different urban centers. These shared design tools and distribution platforms have an effect. Given the proliferation of globally share spatial strategies, it may be possible to generate work that creates friction with these conditions."

With S-281913, Oppenheimer, not unlike some key artists to have employed Institutional Critique in the past, attempts to move the attention of PAMM visitors away from the skeletal or essential pillars of the museum's architecture, and instead highlights its underbelly of minuscule, often invisible inner-workings. For her, their invisibility and the lack of attention paid to them on a daily basis is key. In a text-based outline for the project, she breaks down her focus on the complex ballet of mechanics that are constantly at work within such a structure, bringing together thresholds (doors, hinges windows, latches and locks) and shifts (elevators, revolving doors, escalators, air conditioners, light dimmers, boilers and generators). All of these very small pieces make up the whole of the puzzle that manifests itself into tan enclosed space within which we interact with objects, programs and various forms of stimuli in general. These minute facets thus begin the cranking process of the whole system that allows for the movement of people, air, water, waste and electricity, all of which are intricately mediated by timers, triggers, sensors and logistics.

By utilizing and re-contextualizing PAMM's oft-under-appreciated systemic components, S-2819193 also becomes another example of what Oppenheimer's compendium text, "The Array," initially published in Art in America in the spring of 2014, claims. In this text the artist reiterates the fundamentals of architecture and the factual underpinnings that turn creativity into sustainable reality: namely that a built space is made up of physical (walls, doorways, stairs and floors), and immaterial (sight-lines, sunlight and crowding) components, and that variables such as distance, temperature, speed and direction quantify how such limits affect the people that inhabit a space. In this way, the work cleverly takes up the unseen air chamber space beneath the gallery's floor plane, in which S-281913 will essentially be hidden. Additionally, the insertion of a large beam positioned in between the concrete and the metal decking that supports the space's floor will complicate the viewer's point of view and their experiential orientation. Through this architectural reshuffling, the work creates the illusion of a binary at play, while the exhibition space remains technically undivided. From this perspective, S-281913 operates like a switch of sorts.

When discussing S-281913, she expands upon her conception of the social role of a building and therefore of The Array, stating, "I am interested in how the programmatic agenda of museums is intertwined with the political requirements of a city... In this context, architecture offers institutions a branding opportunity. The branding of the building seems to emphasize the significance of the architecture and the architect, while flattening the building both conceptually and spatially. My work aims to counteract the tendency towards spatial flattening and sameness."

With "sameness" in mind, PAMM itself describes Oppenheimer's intervention via S-281913 as one that, again, calls to action two implemental switches that rotate the glass elements that connote transparency in contrast to the lighting conditions within the exhibition space of the second floor of the museum. The result of this inversion alters and complicates one's viewing position and likewise his or her impressions of what other works of art are on view. While all of this seems deeply tethered to the museum itself, and the presence of the people that occupy it and make it a worthwhile endeavor, it is interesting to consider the language Oppenheimer uses in "The Array," in which she describes the aforementioned as, "simultaneous and suspended, continuous and discrete." Perhaps in her attempt to truly remain site-specific, Oppenheimer takes on not only the logistics of the PAMM building but more intuitively, its mood, which undeniably aims to blur distinctions, rendering the visitor more lost than found.

2015

December

Petra Cortright, Casey Jane Ellison, Ann Hirsch, Yung Jake, Jason Musson, Ryder Ripps

Steve Turner

6830 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles

December 12 - 30, 2015

PRESS RELEASE:

The Real World brings together six emerging artists– Petra Cortright, Casey Jane Ellison, Ann Hirsch, Jayson Musson, Ryder Ripps and Yung Jake. While each artist has a distinctive practice and body of work, they all share a common history of having developed their practices online. As their practices matured, they also began to create paintings, video, sculpture and performances for brick-and-mortar galleries. Their practices function both online and in real space and time, mirroring the dual nature of life as currently lived—we all spend more and more time online and would rather lose our wallets than our smartphones. As the Internet continues to become more incorporated into daily life, users not only go online to search, shop and surf the net, they also engage in all kinds of online-only social behavior. This includes the pursuit of friends, collaborators, dates and even spouses. Through the intimacy that builds as users insert so much personal information into their smartphones, their level of comfort with publicly broadcasting such private content broadens. We see it ALL—young women putting on make-up and pouting seductively as they would in their own mirrors; “belfies” where people jiggle and celebrate their asses; all kinds of inside jokes-turned-memes where catch phrases are attached to embarrassing images of celebrities or funny looking kittens; and the incessant looping of gifs overlaid with pop music.

These six artists, having come of age in the 2000s, take this type of reflective lifestyle as a given. As such, their work often includes various forms of self-portraiture that mimics the selfie-generation. Much like reality television, Instagram, Periscope and Youtube stars who use social media to gain an instant, vast audience, emerging artists are also using online platforms to appeal to mass audiences in similar fashion. However unlike Internet celebrities whose fame often stems merely from the sheer volume of content they post, these artists use irony and satire to critique the self-indulgence and senselessness rampant in online social networks.

In addition to their successes online, which are generally measured in numbers of followers and likes, these artists have simultaneously developed works for the physical space of the white cube. The Real World presents works from both realms. In so doing, the exhibition reveals how blurred the distinctions between the way we live in real life and the way we live online have become. At the same time, we see through each artist’s work, that viewing objects in space is still a significant way to understand art and culture that cannot be replaced by the Internet experience.

Los Angeles-based Petra Cortright began her online practice in 2008, when she posted her now famous YouTube videos that functioned as looping portraiture. Using default design tools popular at the time, Cortright both enhances and obscures her own image. In The Real World, Cortright will present a new short video that harkens back to her YouTube roots, utilizing a rainbow effect that showers colorful, abstract streams across the screen. Also on view will be one of Cortright’s paintings in which she eliminates her likeness while presenting the aesthetic of her videos onto a two-dimensional surface.

Casey Jane Ellison, also based in Los Angeles, works as an artist, stand-up comedian and talk show host. She often abstracts and roboticizes video footage of herself reciting comedy routines that she also performs at local clubs and in galleries. The Real World presents Part ll of Ellison’s single-channel video installation, It’s So Important to Seem Wonderful (2014), first exhibited earlier this year in the New Museum’s Triennial. Here Ellison has expanded the installation to include three channels that seem to be speaking to each other.

Los Angeles-based Ann Hirsch has made work about reality television and even appeared in a dating-themed VH1 show in 2010. Decidedly feminist, Hirsch’s videos, online performances and recent body of drawings, tackle the complexities of what it means to be a woman and an artist today. She will present two new drawings in The Real World that were first conceived during therapy sessions in early adolescence. Hirsch will also present a new video wherein she appears to be giving birth.

New York-based Jayson Musson is widely known for the character Hennessy Youngman whose series, Art Thoughtz, was first presented on YouTube in 2010. Hennessy is a cultural critic who humorously speaks directly to the Internet on art world topics including “How To Be A Successful Artist;” “How To Be A Successful Black Artist;” “On Beauty” and on “Relational Aesthetics.” In addition to presenting Art Thoughtz, Musson will also present one of his new Coogi Sweater paintings.

Ryder Ripps, also based in New York, has a diverse practice that incorporates a broad array of activities. A skilled programmer and self-proclaimed “Internet archeologist,” Ripps is the Creative Director of his web design company, OKFocus and has also co-founded several other online platforms including Dump.fm. Popularized in 2010, Dump.fm is known for its outrageous contributors and spontaneous, free-flowing format. The Real World will juxtapose Ripps’ work as both a programmer and artist by exhibiting a live feed of Dump.fm in its current state alongside a new series of digital prints based on face detection surveillance software systems.

Yung Jake is a Los Angeles-based artist who creates video, sculpture, painting, music and performance. His work often addresses the social environment of the Internet. In Datamosh, his 2011 rap video, his lyrics include a reference to another artist in The Real World “…makin’ gifs on the web like Ryder Ripps.” Yung Jake uses the visual language and style of the Internet across his diverse output. He cuts, copies, pastes, crops, edits and airbrushes imagery that floats freely throughout cyber networks. For The Real World, Yung Jake will present a new sculpture that features advertising imagery for the alcohol brands Cîroc and Hypnotq alongside a two-channel video installation of a recent music video.

-Courtney Malick

Images:

Moderator, panel discussion with Sean Raspet, Encyclopedia Inc., and Lucy Chinen, In the Flesh Part l: Subliminal Substances, Martos Gallery, Los Angeles

Images:

Lucy Chinen, "future foods," presentation documentation, 2015

Summer Writer-in-Residence

The Miami Rail, Fall issue, 2015

Chayo Frank, AmerTec Building, Hialeah, Florida, 1969

My relationship with Miami’s contemporary art scene began not with Art Basel Miami Beach, but with a site-specific art project in which I participated, spending a week filming with my longtime friends Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch. This was in 2009, and their house where most of the shoots took place was in Little Haiti. When I look back on that first trip to Miami now, it is shocking to me how little I knew about what was going on in contemporary art in the city. What’s more, when I look back at the video work that Trecartin and Fitch produced during the year that they spent in Little Haiti, it is surprising how little of the actual place itself seeps into the stories, characters, or even the sets and backdrops of the movies that they made there. Even more surprising today is that, with the exception of Art Basel and the satellite art fairs in early December, it seems that even still the depth and historical lineages of Miami’s relationship to contemporary art is lost on many.

I too am guilty of this offense, usually coming to Miami during that one week in December when much of the artwork that one takes in has nothing to do with Miami itself and is only temporarily implanted there from more international “art cities” like New York, Berlin, London, Paris, and more recently, Los Angeles. However, having been given the opportunity to spend more time there this summer—in the off-season, no less—and meet with a handful of artists, gallerists, curators, and writers, it is amazing to me that Miami remains somewhat of a contemporary art secret, or even haven. Perhaps it’s best this way, but nonetheless, the more I learned, the more impressive the area’s connections to an art historical past shone through.

GucciVuitton, Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, 2015

One of the best examples of this that I saw is the exhibition GucciVuitton, curated by the artist-run gallery of the same name, which is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Miami (ICA) through September. The exhibition itself is unique for many reasons, presenting content in ways I have never seen or heard of elsewhere. For one thing, it is ultimately a retrospective of a gallery’s history, a rather strange endeavor in and of itself. Secondly, the exhibition design cleverly utilizes the lack of proper exhibition space the museum currently has available in its temporary building as its permanent home is being constructed. The directors of GucciVuitton, each of whom maintains his own independent artistic and design practice, decided to activate the interior of the lobby space, not only on the ground floor, but by installing a transparent, cage-like scaffolding all the way up to the top, fourth floor. In this way, viewers do not enter a gallery to see works installed on its walls or in its white cube space, but instead can only access the works from behind the glass through which one would normally peer downward from the second, third, and fourth floors to see the atrium-like lobby below. Each of these windows now acts as a secondary frame, detaching viewer from artwork, creating the sensation of window-shopping. Moreover, visitors are afforded the rare viewpoint of seeing nearly the

entire show all at once, including the backs of works installed on the opposite side of the building.

While the exhibition design is also unusual in its ability to drastically alter the perspective of the viewer in ways I have never before experienced, GucciVuitton, which has taken works from each of the gallery’s past twelve shows, also serves as an important history lesson. Here attention is called to a wide range of artistic traditions, cultures, and figures throughout the entire southeastern region and its neighboring countries. This includes little-known and longstanding trajectories throughout Floridian history, such as Florida landscape painting, seminal figures and constructs in organic architecture, and sculptures and paintings directly related to the felt prevalence and mythologies of Haitian Vodou. This thus expands and reinforces these lesser-known artists and the cultural lineages from which they draw. Certain artists featured in the exhibition were especially revelatory. For example, organic architect and sculptor, Chayo Frank, whose career began in the mid-1960s in Miami when he designed the unusual AmerTec Building, which is today considered a cultlike architectural

landmark.

Though trained as an architect, during the construction of the AmerTec Building, which favors bulbous, curved forms that emulate those naturally found in plant and sea life, Frank also became interested in creating similarly organic sculptural forms with clay. Some of these small-scale sculptures, which made up his solo show at GucciVuitton in the summer of 2014, are on view at ICA and clearly recall the colorful, sci-fi, and otherworldly aesthetic popular in the 1970s. While relationships can easily be made between Frank’s work and that of other ceramic sculptors like Ken Price, most notably, his is clearly rooted in the natural imagery, colors, and forms found in the tropical Floridian landscape.

Another great example of an artist whose work may be lesser known, but undoubtedly holds deep significance in Miami, the greater South Florida area, and especially throughout its Haitian subcultures, is Port-au-Prince-based sculptor Guyodo. Guyodo’s artist group, Atis Rezistans, uses items found in junkyards and other household detritus to create “idols,” as they are known—miniature figurines that represent various Haitian Vodou deities. Though the intricacies of the specific traditions to which each figure relates may be lost on some viewers, it is apparent in their installation that they all have a relationship to one another as well as to the viewer gazing in on them through the glass.

Chayo Frank, #12B, 2012, installation view

From the exhibition, Chayo Frank: Sculptures 1969-2012, GucciVuitton, Miami, 2014

Again the sincerity of the idea of place—along with the stories that make up a place—comes to the fore and shapes the work of the individual artist and the overall exhibition as one that is less about the kinds of questions we often see exhibitions attempting to answer, such as, “What does contemporary art look like, or how does it function, today?” or “How are artists’ methodologies shifting in an ever increasingly technologized digital world?” Instead, the exhibition looks inward, which is not to say backward.GucciVuitton seems to be asking viewers to consider where they are in space and time, perhaps how they got there, and how what they see around them in the city of Miami is informed by such histories as those being revisited and recontextualized by the participating artists. This is certainly not to say that Miami has no stake in the larger and broader conversations that perpetuate the überglobalism of contemporary art, nor is it to say that such an expansive and all-encompassing conversation is of no relevance. But rather that perhaps a city like Miami,which continues to dip its toe deeper and deeper into contemporary art’s murky waters—so much so that it is now apparent it will be swimming laps in the years to come—can render itself apart from other major art cities through its less global attributes and selling points.

It is an intriguing contradiction central to the draw of today’s most prominent brand of contemporary art that it tends to champion the universalism of work that speaks to many people in many places all at once and yet applauds those able to reveal the underbelly of the stone unturned, usually found in the geographical and cultural peripheries. The latter point may account, at least in part, for the wafting return of the popularity of abstract painting over approximately the last five years, particularly within the United States. However, to interrogate the peripheral often does not yield to the uncovering of universality. Whether or not this is to be celebrated or critically dissected ought to be taken on a case-bycase basis. However, it should by now be apparent that at least one of the reasons that too much contemporary art looks like a carbon copy of an object or image made in the image of a pre-existing image, is precisely due to this kind of “global” mandate.

Though artists need not consistently approach their work from a site-based perspective, it is not difficult to see that Miami and South Florida represent an unusual part of the United States that

remains somewhat detached in ways that are far divergent from most other “major” art cities. While every year in December Miami invites the global art world onto its beautiful beaches and into its lavish hotels to celebrate another year in nonstop city-hopping for most art professionals and patrons, I hope as its contemporary art institutions and communities continue to grow, it will nonetheless look further inward at what separates it from other places rather than blend more and more seamlessly in with what characterizes the general milieu of contemporary art overall.

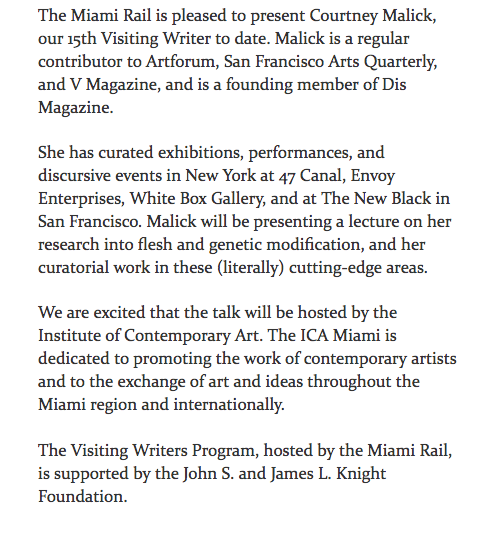

Courtney Malick is a contemporary art curator and writer whose practice focuses on intersections among video, sculpture, performance, and installation. She has curated a group exhibition that deals with inorganic ingestible matter and its potential long-term effects on the human body, which opens at Martos Gallery, Los Angeles, in October.

July

Speaker, “In the Flesh,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

"Thank you all so much for coming!

I will be speaking to you today about an exhibition that I have been piecing together for over a year now, which is tentatively titled, In the Flesh – which is an apropos term, and yes, also the title of one of my favorite Blondie songs, but I am not really set on that title -- I find coming up with titles of exhibitions to be difficult for me in that I usually come up with one right away at the onset of a new idea or project and then even if I know I could probably think of a better one I become strangely married to it and have a hard time thinking of any others as being more fitting

In any case, for the purposes of this talk I will just refer to the show as, In the Flesh, which will take place this fall in Los Angeles at Martos Gallery (whose main space is in NY in Chelsea, and just last summer they opened a new space in LA as well).

The show will include artists whose work relates to inorganic, ingestible elements found in products that include food, beverages, beauty and health items, and also technological devices that emit certain chemicals and radioactivity that are absorbed into our bodies through our skin. These inorganic, potentially harmful, ingestibles include things like GMOs, hormones, pesticides, radiation, plastics and bacteria, all of which are more and more consistently seeping into our bodies, especially as the term “organic” becomes more commonplace and its regulations decrease.

In fact, in doing research for this upcoming show I've learned that the U.S. is one of the only major countries left in the world in which food companies are not obligated to disclose whether or not their products include GMOs or not, and that Whole Foods has a goal of being able to assure their customers that by 2018 no food products that they carry will include GMOs, but that at this time some of them do.

The show will explore the ways in which our bodies are potentially and obviously very slowly adapting and therefore also morphing as a result of this increasing seamlessness between what we think of as purely organic or natural matter, such as skin and flesh (both of humans and animals), and inorganic ingestibles, such as those that I have just mentioned -- and, how such a seamlessness will eventually, over time, alter the forms that human bodies take and the ways that they function.

This project, overall, will be broken into two parts, and thus two exhibitions, so In the Flesh will be the first, and the second will take up issues that are related, but have more to do with the ways that some people are exteriorizing (and in some cases accelerating), this morphing process on their own, through practices like self-body-modifications, bio-hacking, transhumanism, chronic plastic surgery, extreme body building and the use of steroids and other performance enhancement practices like self-doping, "fashion" trends like "bagel-head," (which was popular in Asia a few years ago) or anime or doll face (like the Russian woman known as Fukkacumi), and a general shift towards the more and more plausible reality of human cyborgs, such as new trends like fingertip magnet implants, and an artist named Neil Harbisson who is considered to be the first real cyborg, due to the fact that he is the first person to have implanted an antennae into his skull, which allows him to perceive visible and invisible colors like infrareds and ultraviolets through audible vibrations as well as receive images, and even phone calls directly into his head without the use of a hand held device.

[slide 1]

3D-printed scan of Neil Harbisson by Metropolitian Museum of Art Media Lab, 2015, New York

These ideas that I have been mulling over and researching for the past year, were first sparked by the work of an artist named Ivana Basic, who was born in Belgrade and now lives and works in New York. I first came across Basic’s work while looking at the website for the Brooklyn project space 319 Scholes, in which Basic’s piece, Automata was included in a 2012 group show titled, Not Spring, Not Winter that she actually co-curated with Jack Kalish and Kate Watson.

At that time, Automata was titled, Solid, and has since changed form. But in that show, the piece consisted of a white, plaster blob on a table, inside of which small hammer-like devices called “solenoids” tapped away at the blob’s interior. At the same time, a live feed of the inside of the blob was projected on the wall behind it, and tiny microphones placed inside the blob amplified the sound of its slow, internal breaking. To further anthropomorphize this blob, which resembled to some extent some kind of organic matter or possibly the head of a penis, it was also outfitted with motion sensors, so any time a viewer came too close to it, the tapping would stop. Depending on how often the tapping was stopped by the intrusion of viewers, Automata (then called Solid) would take approximately 3 days to break apart.

I became intrigued by this work, as it related directly to a project I was working on at the time that was about the very gradual and incremental destruction of all forms of convention, belief and rhetoric, which I postulated began with an obliteration of all religion. I had planned that this project, titled To Be Announced, would take the form of an exhibition, but it ended up becoming a long-format essay that I was commissioned to write by Tom Leeser, (head of the MFA New Media Dept at CalArts) for an online journal that he co-founded in association with the school called Viralnet.net.

During the time that I was writing the essay I got in touch with Ivana and then finally had a studio visit with her in New York in the spring of 2014. There I saw these very realistic, fleshy, meat-like sculptures that sometimes incorporated soft materials like pillows and blankets...

[slide 2]

Ivana Basic, Asleep, 2015

Body, feathers, wax, pillows,weight, pressure, silicone

Basic's sculptures were so grotesque and even congenital that I could not get them out of my mind for weeks after our visit. They seemed almost to breath and pulsate (aspects of which she is currently working on making possible). I began to think of them especially while looking at all the raw meat in the butcher’s counters at the grocery store, or whenever I thought of preparing meat at home, seeing commercials for it, etc…

[slide 3 and 4]

Ivana Basic, Disintegration in the direction of something other than death #2, 2014

Hollow body, weight, feathers, pillow, sweat, elastic band, hooks

Ivana Basic, Weight, 2015

Hollow body, weight, wax, silicone, drywall, wood

And this then lead me to pick up an older obsession that I had thought a lot about a few years ago, which is an alleged and controversial disease called Morgellons. This is a disorder in which victims claim that they experience persistent painful and itchy sores on their skin underneath which they find various kinds of stringy, plastic fibers that are suspected to be the results of their bodies rejecting plastics they have ingested, but it is debatable within the medical community whether this is the real cause or if their symptoms are actually the result of mental illnesses known as “delusion parasitosis.”

So these questions about what is really going into the human body and how that is being translated through the body, so to speak, became more and more intriguing to me. At the same time, throughout most of last year, while these ideas were all kind of swimming around in my mind, I was also writing a lot of art criticism, reviewing solo and group shows as well as several art fairs. By the time I got to Miami Basel last December, it became very apparent to me that food in various forms and extensions was becoming more and more prevalent in a lot of the contemporary art that I was seeing across all media, whether it be sculpture, photography, video, painting, installation, ceramics, etc...

I first walked through NADA and then Basel with my friends from Dis Magazine, making my case for my food-art hypothesis and finding that in booth after booth there was another work to back up my claim. So, I wanted to show just a few examples of this, all of which were included in my reviews of NADA and Basel. The first 2 images are from NADA and the others are from Basel.

[slides 5 - 9]

One of the many paintings in Mike Bouchet’s series of close-ups of hamburgers which deals with the health issues and economic stability of the fast food industry

Mike Bouchet, Square Wagner, 2014 (detail)

Laurie Simmons, Walking Petit Four, 1990-91

Sean Raspet, Nc1c(c(OC)=cccc1, 2014

Ajay Kurian, Chicken bone chicken bone (Need), 2014

Nathalie Djurberg, Donut with Purple and White Glaze, 2013

After this trip to Miami and writing the reviews of these fairs, I realized that this connection between art, particularly within sculpture, and the origins and practices surrounding food and consumption, were at the core of my interest in Ivana’s work and that that would in turn create the backbone for this group show at Martos Gallery in LA.

It was in the summer of 2014 that I had been invited by Martos Gallery Director, Taylor Trabulus, to propose a concept for a group show for their new LA space, but it took me until the end of last year to solidify how all of these various elements and the work of several artists that I had continued to explore, (including, Ivana as well as Josh Kline and Sean Raspet) came together.

Josh is someone whose work I had known of since 2011, when I graduated from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College and pieces from one of the installations in my thesis show, by the New York-based collective, Yemenwed (who had a large show of their performances here in Miami at PAMM last year), were brought directly from CCS to a group show in Soho that Josh had curated titled, Skin So Soft, at Gresham’s Ghost (a curatorial project taking place at the time initiated, coincidentally, by Ajay Kurian). The show included Kline’s 2011 installation, Share the Health (Assorted Probiotic Hand Gels).

[slide 10]

Josh Kline, Share the Health (Assorted Probiotic Hand Gels), 2011

Here, Kline installed 3 hand sanitizer dispensers on the wall, each of which contained different liquids that were not hand sanitizer (the first contained acidophilus, which was set in mango and coconut flavored nutrient gel, the second contained cultures taken from New York’s G Train that were set in nutrient gel and the third contained cultures from a New York Chase Bank ATM machine set in nutrient gel). This work immediately caught my eye, after which point I began to follow his practice.

Since then Josh has been making really incredible work that gets at the sort of spliced together nature of much of pop culture’s and mass produced commodities’ creepy underbelly. His 2013 new York solo show titled QUALITY OF LIFE at 47 Canal (which, incidentally, was also the gallery where I curated my very first project in 2009), included many works that have informed my thinking for In the Flesh, some of which will (hopefully) also be included in the show.

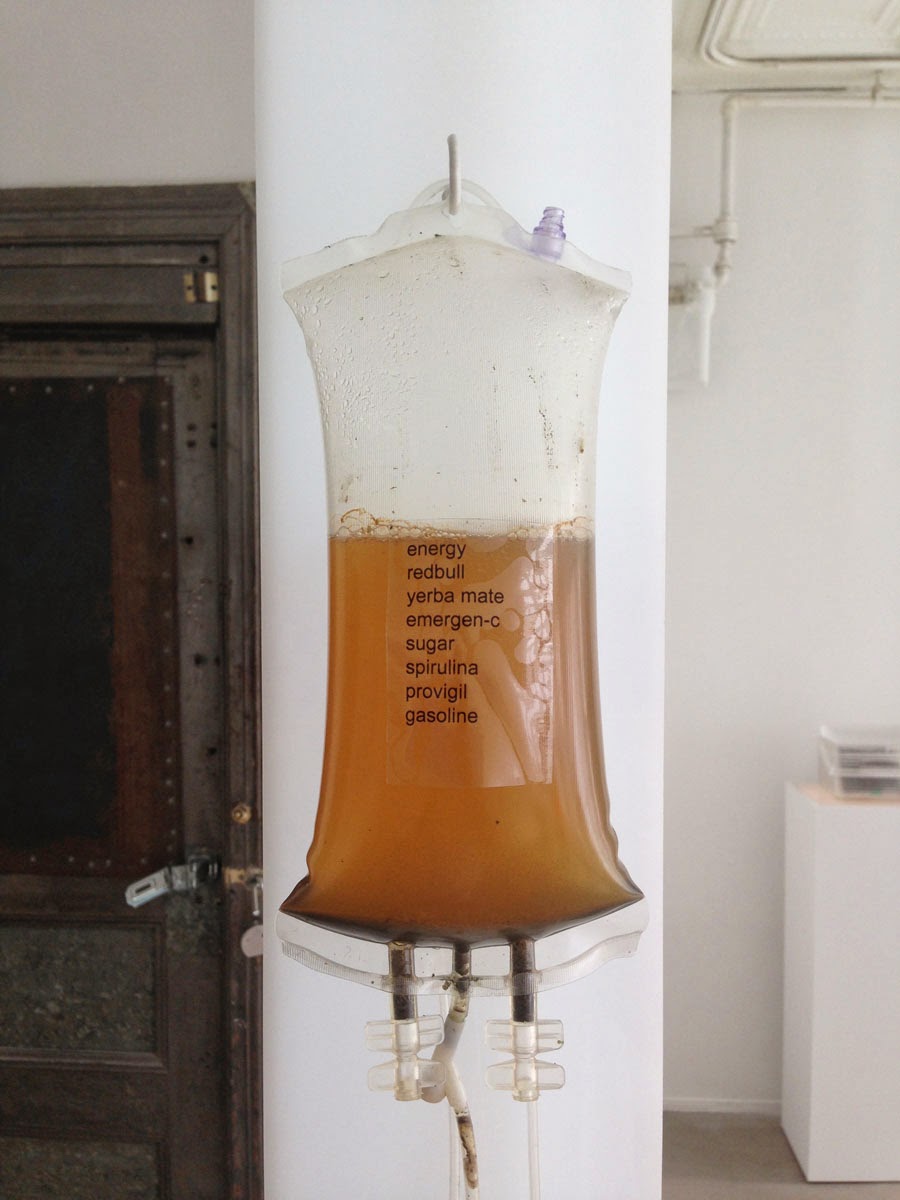

As In the Flesh will aim to decipher, imagine and evoke the act of ingestion, I am very interested in Josh’s series of medical drip IV bags filled with different combinations of substances, similar to his hand sanitizer piece.

[slide 11]

Josh Kline, Energy Drip, 2013 (installation view)

Kline also used medical plastic bags and coolers for a piece made with human blood doped with Wellbutrin, titled, Think Strong

[slides 12 and 13]

Josh Kline, Think Strong, 2013

In an earlier solo show at 47 Canal in 2011, titled, Dignity and Self Respect, Kline made a series of casts in flesh colored silicone that made up the installation, Creative Hands (an image of one of such works that was used for the invitation for this very talk!)

[slide 14]

Josh Kline, Creative Hands, 2011, installation view

Photographer's Hand with Digital Camera (Marcelo Gomes), Studio Manager's Hand with Advil Bottle (Margaret Lee), Retoucher's Hand with Mouse (Jasmine Pasquill), Curator's Hand with Purrell (Josh Kline), DJ/Designer's Hand with IPhone (jon Santos)

pigmented silicone

This piece is one of Kline’s that particularly resonated with me and that I am really excited to exhibit in In the Flesh, because, although rather subtly, the longer I look at it and think about it, the more it gets at the core of this idea of seamlessness that I keep coming back to in terms of the ways that both our bodies and brains are changing as a result of the ways that we assimilate our technological - and especially mobile devices like our smartphones - with our bodies and skin. Im sure Im not the only one who has a knee jerk reaction to assume that my iphone is already in my hand sometimes when I am talking about something and want to either reference a photo or forget a word or name and literally, instinctually turn straight to the palm of my hand to find the information that I am looking for.

I think this phenomenon was well summed up in an essay titled “Digital Handwork,” published last summer on Rhizome, written by Kerry Doran and Lizzie Homersham, in which they reflect on this series by Kline by saying, “In contrast with the machinery of large scale industry, the devices we use for immaterial labor are sleek and pocket-sized, ergonomically built and anthropomorphized. Yet they reshape the hand in crippling fashion, limiting its activities to a set of patented gestures.”

For me that quote really begins to get at the way that our familiarity and dependence on such devices effects certain parts of our bodies, but we also see that they have equal effects on the ways that our minds work, and how we sort, store and configure information. There have also been recent studies that show that the function and ability of humans' short term “working” memory, has decreased significantly as the need to store singular or incremental information like names, dates recent events, etc. has become somewhat obsolete.

In that sense I think of works like Creative Hands as a way to visualize the bridge between the 1st and 2nd parts of this show that intend to demonstrate, in abstracted ways of course, the trajectory from interior to exterior effects of the impetuses and manifestations of the increasing levels of artificiality that we are accepting, not just into our daily lives, but physically into our bodies themselves, and furthermore into our actual genetic make up.